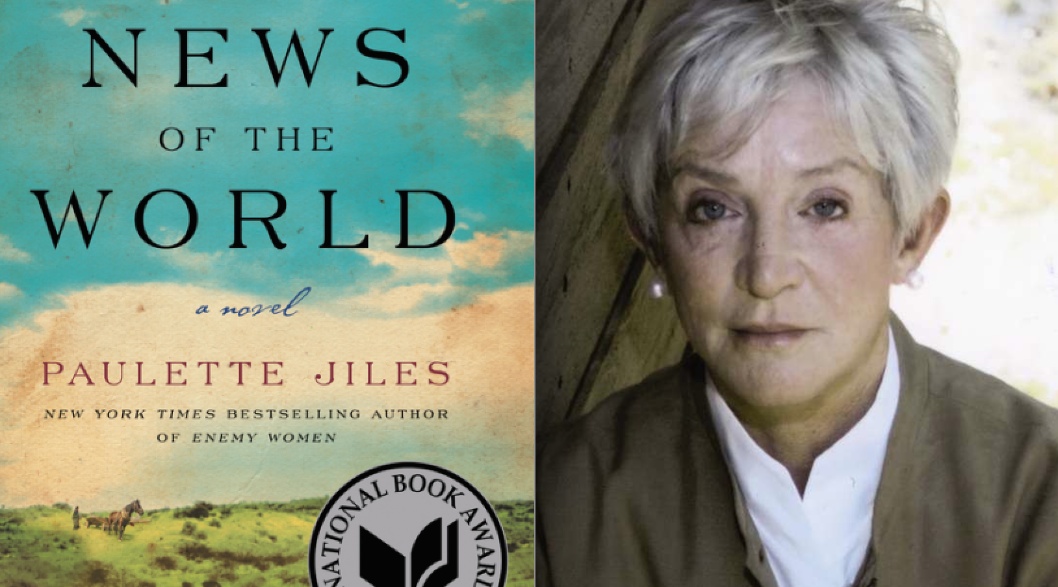

Ending with Defiance: Paulette Jiles on “News of the World”

In the National Book Award finalist News of the World, elderly, genteel Captain Jefferson Kyle Kidd, a former soldier and onetime printer, makes his living traveling through post−Civil War Texas with a sheaf of newspapers, reading for dimes to audiences hungry for outside news.

News of the World

News of the World

In Stock Online

Hardcover

$20.49

$22.99

The former Johanna Leonberger, a ten-year-old German girl taken captive by the Kiowa in a brutal raid, is now by all measures Kiowa herself. She’s traded back for four blankets and a set of silver only when the encroaching U.S. Army threatens violence if all captives are not returned. When an aunt and uncle offer a $50 gold piece for Johanna’s safe return, Captain Kidd reluctantly takes the job.

Their uneasy alliance is also a portrait of the American West — a singular creation, born of a cataclysm. It’s familiar territory for Jiles, whose novel The Color of Lightning tells the story of real-life cowboy and Texas freighter Britt Johnson, the former slave who rescued his own family from the Kiowa, then went on to retrieve other captives. Johnson makes a brief appearance in the novel — an old friend, he’s the one who asks Kidd to take the job.

I spoke with Paulette Jiles about Britt Johnson’s legacy, researching antique rifles on YouTube, and quotation marks in British novels. —Lizzie Skurnick

The Barnes & Noble Review: I’m fascinated by the notion that children who are taken captive turn into Indians. What are your thoughts about how the changeover occurred?

PJ: Did you read Scott Zesch’s The Captured? What he pointed out is that many of these captives were really lost, because by the time they grew up and matured, especially the men, into warriors, the Comanche were confined to the reservation, so that whole wonderful, free life of chasing the buffalo was finished.

BNR: Where did you learn the Kiowa songs — for instance, the Kiowa song Johanna sings when she walks alongside the wagon?

PJ: There’s a wonderful book called Remember We Are Kiowa, which included many phrases, many stories, including the one about the cicada singing. And on the International Language Institutes site, they have sample tapes from different languages all over the world. I thought, “Oh, can I just get lucky here?”

BNR: In Johanna’s case, she goes from hostile to having a sense of humor.

PJ: You have to remember that gunfight scene is seminal. She’s a fighter herself, and the two of them bond, so she’s more willing to relearn Western, civilized ways.

BNR: And to not scalp. Speaking of which, how did you research the guns in that scene?

PJ: I live out in the country by myself, and I have an old Mossberg .20 gauge bolt action. I keep it for varmints. That’s why I gave the Captain a .20 gauge. I’m not even sure they had a bolt action in 1870. I think it would have been sort of a lever, then you load the . . . you know what I am talking about?

BNR: You might as well be speaking Kiowa.

PJ: Have I lost you? I looked up “Antique 20 gauge shotgun” on YouTube. One of the videos was a bunch of young guys out in a dump, shooting at old televisions and microwaves, seeing what kinds of things they could stuff down into a .20 gauge shell. They just blew this microwave apart with frozen gummy bears. And one of them said, “A U.S. dime is the only coin that will fit into a .20 gauge shell.”

BNR: I am fascinated on how much research you did on the Internet with this. Was the bulk of your research on the Internet?

PJ: With the exception of the captive narratives.

BNR: I pictured you’d have a library of books for each work.

PJ: You look for what you need. So when [Kidd] buys a wagon to go south, he’s been carrying a pack pony with him, but he can’t do that with a small girl, so he has to get a wagon. I don’t want a covered wagon, first of all because it would be too large, and he would need a four-horse team. So I went through images and found a little excursion wagon.

BNR: I had never heard of the job of a newsreader. How did you choose that role for him?

PJ: The husband of a friend mentioned that his great-grandfather was a newsreader. I put him into The Color of Lightning, but he was too good a character to just leave, and I thought, this person deserves a book to himself.

BNR: That brings us to Britt Johnson. Can you tell me about how you came across him?

PJ: I was considering a sequel to Enemy Women, and I came across the famous Elm Creek Raid of 1863, involving Britt Johnson. He was a true hero and very brave. He rescued his wife and two children, and no one knows how he did it. Apparently they used his story as the basis for The Searchers, only they changed him to a white man, and changed his wife, daughter, and son to a niece.

BNR: What’s the difference between poetry and prose for you, as a writer?

PJ: The basic unit of poetry is a phrase, and the basic unit of prose is supposed to be a sentence. So I had a long training in sounds, and searching out exactly the right word, and not being content with a word that was halfway okay. Nor could I be content with an awkward rhythm.

BNR: There’s a technical question I like to ask authors of westerns. Often, you don’t use quotation marks around dialogue. Is that a deliberate choice?

PJ: In older British novels, they use dash lines. I really like that a lot. And when I picked up Cormac McCarthy, who simply threw them away, I thought, “That’s so daring.” So I did that for Enemy Women. I received so many complaints. I put them back in for Color of Lightning, chicken that I am. Now I’m reading some of the reviews on Goodreads, complaining about it. So I went to Cormac McCarthy, The Road, All the Pretty Horses. Not one complaint.

BNR: I’m not sure if you realize, but this book is a heart-stopping experience. I was going to kill you if something bad happened to Johanna.

PJ: You were going to come to Utopia and find me?

BNR: Exactly. Because obviously, The Color of Lighting does not have a happy ending.

PJ: I had a friend here in Utopia who told me, “Please, please don’t tell me Britt gets killed.” Sorry. I can’t help it. It was a real person.

BNR: Was it a choice to make News of the World such a happy book?

PJ: The fashion has been in literary fiction for the depressing ending, and for more or less passive characters who have terrible things happen to them. The ending is sort of out of defiance. Kidd is a strong character and very intelligent. He was a man of honor. He was going to help her and protect her no matter what. So why not have a happy ending? Is there a law?

The former Johanna Leonberger, a ten-year-old German girl taken captive by the Kiowa in a brutal raid, is now by all measures Kiowa herself. She’s traded back for four blankets and a set of silver only when the encroaching U.S. Army threatens violence if all captives are not returned. When an aunt and uncle offer a $50 gold piece for Johanna’s safe return, Captain Kidd reluctantly takes the job.

Their uneasy alliance is also a portrait of the American West — a singular creation, born of a cataclysm. It’s familiar territory for Jiles, whose novel The Color of Lightning tells the story of real-life cowboy and Texas freighter Britt Johnson, the former slave who rescued his own family from the Kiowa, then went on to retrieve other captives. Johnson makes a brief appearance in the novel — an old friend, he’s the one who asks Kidd to take the job.

I spoke with Paulette Jiles about Britt Johnson’s legacy, researching antique rifles on YouTube, and quotation marks in British novels. —Lizzie Skurnick

The Barnes & Noble Review: I’m fascinated by the notion that children who are taken captive turn into Indians. What are your thoughts about how the changeover occurred?

PJ: Did you read Scott Zesch’s The Captured? What he pointed out is that many of these captives were really lost, because by the time they grew up and matured, especially the men, into warriors, the Comanche were confined to the reservation, so that whole wonderful, free life of chasing the buffalo was finished.

BNR: Where did you learn the Kiowa songs — for instance, the Kiowa song Johanna sings when she walks alongside the wagon?

PJ: There’s a wonderful book called Remember We Are Kiowa, which included many phrases, many stories, including the one about the cicada singing. And on the International Language Institutes site, they have sample tapes from different languages all over the world. I thought, “Oh, can I just get lucky here?”

BNR: In Johanna’s case, she goes from hostile to having a sense of humor.

PJ: You have to remember that gunfight scene is seminal. She’s a fighter herself, and the two of them bond, so she’s more willing to relearn Western, civilized ways.

BNR: And to not scalp. Speaking of which, how did you research the guns in that scene?

PJ: I live out in the country by myself, and I have an old Mossberg .20 gauge bolt action. I keep it for varmints. That’s why I gave the Captain a .20 gauge. I’m not even sure they had a bolt action in 1870. I think it would have been sort of a lever, then you load the . . . you know what I am talking about?

BNR: You might as well be speaking Kiowa.

PJ: Have I lost you? I looked up “Antique 20 gauge shotgun” on YouTube. One of the videos was a bunch of young guys out in a dump, shooting at old televisions and microwaves, seeing what kinds of things they could stuff down into a .20 gauge shell. They just blew this microwave apart with frozen gummy bears. And one of them said, “A U.S. dime is the only coin that will fit into a .20 gauge shell.”

BNR: I am fascinated on how much research you did on the Internet with this. Was the bulk of your research on the Internet?

PJ: With the exception of the captive narratives.

BNR: I pictured you’d have a library of books for each work.

PJ: You look for what you need. So when [Kidd] buys a wagon to go south, he’s been carrying a pack pony with him, but he can’t do that with a small girl, so he has to get a wagon. I don’t want a covered wagon, first of all because it would be too large, and he would need a four-horse team. So I went through images and found a little excursion wagon.

BNR: I had never heard of the job of a newsreader. How did you choose that role for him?

PJ: The husband of a friend mentioned that his great-grandfather was a newsreader. I put him into The Color of Lightning, but he was too good a character to just leave, and I thought, this person deserves a book to himself.

BNR: That brings us to Britt Johnson. Can you tell me about how you came across him?

PJ: I was considering a sequel to Enemy Women, and I came across the famous Elm Creek Raid of 1863, involving Britt Johnson. He was a true hero and very brave. He rescued his wife and two children, and no one knows how he did it. Apparently they used his story as the basis for The Searchers, only they changed him to a white man, and changed his wife, daughter, and son to a niece.

BNR: What’s the difference between poetry and prose for you, as a writer?

PJ: The basic unit of poetry is a phrase, and the basic unit of prose is supposed to be a sentence. So I had a long training in sounds, and searching out exactly the right word, and not being content with a word that was halfway okay. Nor could I be content with an awkward rhythm.

BNR: There’s a technical question I like to ask authors of westerns. Often, you don’t use quotation marks around dialogue. Is that a deliberate choice?

PJ: In older British novels, they use dash lines. I really like that a lot. And when I picked up Cormac McCarthy, who simply threw them away, I thought, “That’s so daring.” So I did that for Enemy Women. I received so many complaints. I put them back in for Color of Lightning, chicken that I am. Now I’m reading some of the reviews on Goodreads, complaining about it. So I went to Cormac McCarthy, The Road, All the Pretty Horses. Not one complaint.

BNR: I’m not sure if you realize, but this book is a heart-stopping experience. I was going to kill you if something bad happened to Johanna.

PJ: You were going to come to Utopia and find me?

BNR: Exactly. Because obviously, The Color of Lighting does not have a happy ending.

PJ: I had a friend here in Utopia who told me, “Please, please don’t tell me Britt gets killed.” Sorry. I can’t help it. It was a real person.

BNR: Was it a choice to make News of the World such a happy book?

PJ: The fashion has been in literary fiction for the depressing ending, and for more or less passive characters who have terrible things happen to them. The ending is sort of out of defiance. Kidd is a strong character and very intelligent. He was a man of honor. He was going to help her and protect her no matter what. So why not have a happy ending? Is there a law?